RESEARCH EXCHANGE

Should we tackle the 'root causes' of migration? Likely no.

Author

About

Jessica Hagen-Zanker and Jørgen Carling

migration governance

While the hardships that can spur people to migrate cannot be ignored, the well-intended idea of tackling the ‘root causes’ of migration can easily yield misguided policy.

In this short, we share new evidence on the logic of root causes based on the ‘Aligning Migration Management and the Migration–Development Nexus’ (MIGNEX) project’s extensive research over five years in 25 local communities across ten countries in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

Why address root causes?

There is no clear and common definition of root causes, so MIGNEX proposed the following: root causes are widely experienced hardships, to which migration is a possible response, that are perceived to be persistent, immediately threatening, or both.

As a policy choice, dealing with root causes may be attractive because migration flows can be hard to manage at the border, and even more so if migrants become irregular residents. Attempts to keep migrants out have contributed to an estimated 70,000 deaths during the past decade.

While views on migration diverge, there is widespread frustration and outrage over this situation across the political spectrum.

The prospect of ‘tackling the root causes of migration’ seemingly offers hope. It’s a long-term and daunting objective, but at least it has broader political appeal than the increasingly hollow call for ‘safe routes’, given the hostile discourse in destination countries that makes the creation of such routes unlikely.

Our research shows that the sweeping notion of managing migration by dealing with its root causes is at odds with how migration works and runs the risk of spurring bad policy.

The flawed logic of root causes?

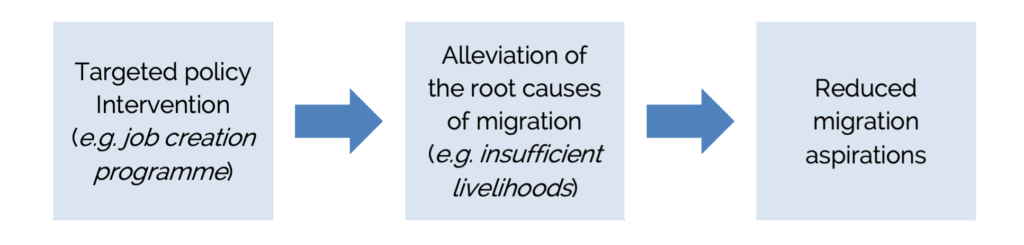

The basic logic of the root causes approach is that there are hardships that produce migration aspirations, meaning desires or plans to move to another country. So, if policy interventions can alleviate these hardships, people would want to stay, or so the argument goes.

The basic logic of tackling the root causes of migration

But does this logic conform with peoples’ actual behaviour and decisions about their own migration? Working with a large team of colleagues, we surveyed more than 13,000 young adults about their lives, their communities, and their thoughts and feelings about migrating or staying. One of the novelties of our approach was being able to capture the flourishing, demise, or other characteristics of local communities, and not just indiscriminate national averages.

Findings

Three broad findings are particularly relevant to counter the idea of tackling the root causes of migration.

- The finding that surprised us the most was that the drivers of migration aspirations differ so much from one community to the next. One might think that people who see local livelihoods as scarce or insufficient would be more keen to migrate, but that holds true in fewer than a quarter of the communities we studied.

- It is also striking that some apparent ‘root causes’ work in counterintuitive ways. For instance, people who are poorer, or live in poorer communities, are less likely to have migration aspirations than better-off people in better-off communities.

- The effects of root causes are often dwarfed by other drivers of migration desires. In particular, people who have ties with current or former migrants are much more likely to want to migrate.

These findings, based on our extensive data and statistical analyses, help us to understand the patterns of global migration and challenge the notion of ‘tackling root causes’ in three ways.

- Even in the best-case scenario, policy interventions are likely to be ineffective unless they are carefully tailored to specific contexts.

- Policies that successfully reduce poverty and thus a supposed key ‘root cause’ could actually raise migration aspirations, rather than lower them.

- Migration aspirations are likely to remain shaped by factors that are beyond the scope of migration policy.

To illustrate the scale of the challenge, the World Bank estimates that creating employment through targeted investments could cost €30,000 per job in a middle-income country. Similarly, top-down anti-corruption measures often have a high cost and a small impact.

Good policy can, of course, contribute to prosperity and well-being in the long term. But the relevant time horizon is over several decades, which means that the relevance of root cause approaches to the more immediate demands of migration policymaking can fade.

How can we navigate this dilemma?

We draw three key implications from our research to help navigate this dilemma:

- Don’t make false assumptions about the reasons why people want to migrate. Even factors that, on average, tend to make a difference will often be inconsequential.

- Let development policy be steered by development outcomes and not by its presumed effects on migration. Measures to address the root causes of migration could be wasteful as development policy and inefficient as migration policy.

- Address the consequences of barriers to migration. If people are barred from seeking prosperity or security elsewhere, it is all the more important to support foundations for better local futures.

- Don’t make false assumptions about the reasons why people want to migrate. Even factors that, on average, tend to make a difference will often be inconsequential.

Jessica Hagen-Zanker is a Senior Research Fellow at ODI Global, where she heads up the Migration and Displacement Hub, and a Global Fellow at Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO).

Jørgen Carling is a Research Professor at the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) and Co-Director of the PRIO Migration Centre.

Learn more:

- Policy Brief – What are the root causes of migration?

- Background Paper – Tackling the root causes of migration

- Project Report – New insights on the causes of migration

- Journal Article – The multi-level determinants of international migration aspirations in 25 communities in Africa, Asia and the Middle East

Submit your idea for a ‘short’ to be featured on the Co-Lab.