RESEARCH EXCHANGE

Do warnings against migration actually work?

Author

About

Nicolás Caso Castellón and Jørgen Carling

research

Posters, videos, ads, T-shirts, and songs filled with warnings about irregular migration have become a standard feature of migration policy. The United States has poured resources into campaigns designed to instill fear about the risks of irregular migration. Meanwhile, the EU Commission committed €10 million over the next four years for similar efforts. But do such campaigns actually work? Our research suggests that they might not be effective.

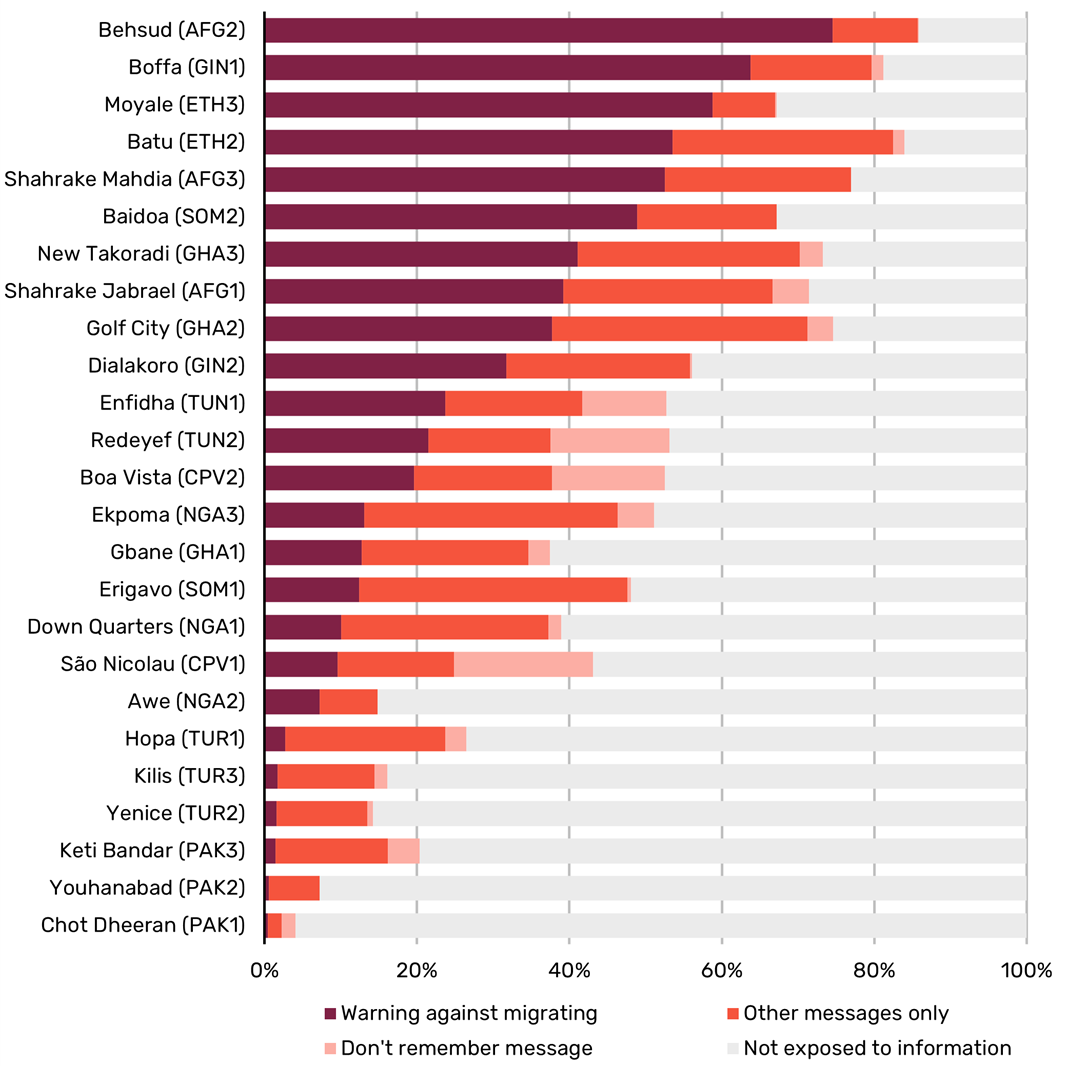

Using data from interviews with over 13,000 young people across 25 communities in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, we wanted to find out whether public information campaigns are changing minds or just making noise.

What we did

The survey, known as the MIGNEX survey, took place between 2020 and 2021 and asked whether young adults have seen or heard any information about migration in the past year, and if so, what stuck with them (more information about the MIGNEX survey at the end of this short).

We found that exposure to migration information varies widely, and most messages tend to be warnings against migrating. However, these campaigns represent just one piece of a much larger puzzle. Importantly, such warnings do not appear to affect people’s aspirations to migrate—and in some cases, they might even backfire.

What we learnt in five takeaways

1. Exposure to migration information varies greatly: In some places, only 4% of people have seen or heard any migration information. In others, it is as high as 86%.

2.Most messages are just warnings:

Across the board, the main message young people remembered was simple: don’t go. Among those who’d seen or heard migration information, about 50% said the core message was a warning against migrating. Other types of messages—such as guidance on how to migrate legally or information about migrants’ rights—were mentioned much less frequently.

3. These campaigns are only one piece of the puzzle:

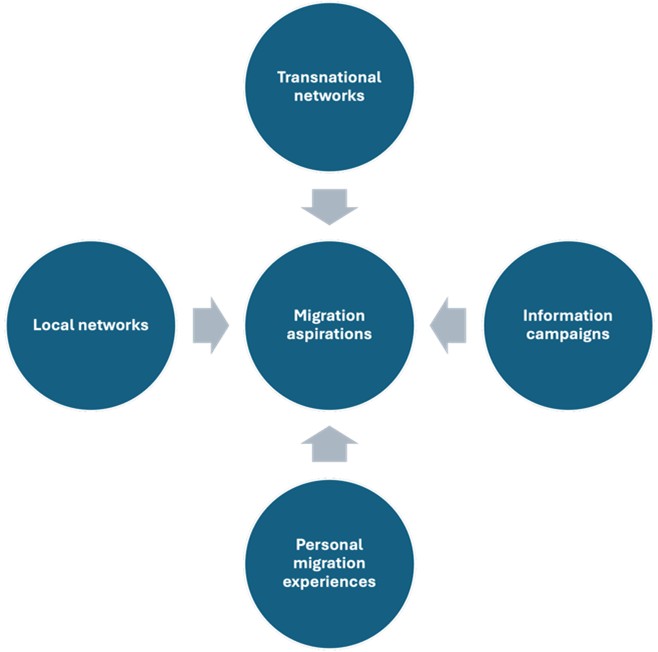

Migration information campaigns are just part of a bigger information landscape. People reported encountering a range of other messages, including explanations of what migration is, reasons why people migrate, warnings about migrants in destination countries, and tips on how to migrate. So, while governments may focus on warnings, that’s not all people are hearing, and it’s often not the full story. We should also acknowledge the strong presence and role that diasporas and transnational networks have in this landscape and how they influence aspirations to move digitally. Information coming from a “known source” can come across as being more reliable.

4. Warnings don’t change aspirations: Being exposed to warnings against migrating doesn’t seem to be associated with declared lower migration aspirations. Based on our regression analyses, we found no consistent link between seeing/hearing these messages and a lower desire to migrate. In fact, in some places, the opposite can even happen.

5. Sometimes, warnings might backfire: Where we did find an effect, it was more often a rise in migration aspirations. Why? This could be because warnings might make migration feel more real or urgent, or because they portray life abroad—despite the risks—as still more appealing than staying. Additionally, these messages often fail to offer a convincing alternative at home, which may further reinforce the desire to leave.

So, what should be done instead?

Spreading information about the risks of irregular journeys might seem harmless and sensible. But besides their apparent ineffectiveness, information campaigns can be ethically fraught. A few ground rules should be followed:

– Don’t deceive. Some campaigns obscure their sources of financing or otherwise mislead about the policy interests that drive them.

-Don’t undermine rights. People with a genuine need for protection have the right to seek it in a safe country and should not be led to think otherwise.

– Don’t demonise smugglers in general. Campaigns often present smugglers as inherently evil. But they are often the only means of reaching safety, and migrants are faced with the challenge of identifying reliable ones.

Looking beyond deterrence campaigns, more can be done to ensure safe pathways for those who seek opportunities abroad. Even when there is demand for migrant labour, potential migrants are often vulnerable to exploitation and fraud. When regular pathways are also risky, irregular options might not seem much worse.

Learn more:

MIGNEX – Aligning Migration Management and the Migration–Development Nexus – is a five-year research project (2018–2023) with the core ambition of creating new knowledge on migration, development and policy. It involves researchers at nine institutions in Europe, Africa and Asia.

Nicolás Caso Castellón is a PhD fellow at UNU-CRIS and at Ghent University. His research focuses on conflict, disasters, migration and the intersection between them.

Jørgen Carling is a Norwegian researcher specializing on international migration. He holds a PhD in Human Geography from the University of Oslo and is Research Professor of Migration and Transnationalism Studies.

Submit your idea for a ‘short’ to be featured on the Co-Lab.